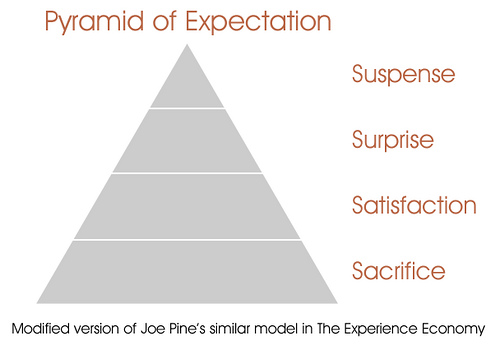

Yesterday we went through The Pyramid Of Expectation, and understanding how providing compelling experiences (or failing and providing awful ones) is based on your ability to meet expectations. In actual fact, we discussed that it’s no longer enough to meet customer’s expectations (this is merely customer satisfaction), you have to move into the arena of exceeding expectations (which is customer surprise.)

Today I’m going to layout how to go beyond even exceeding expectations and begin to get into the realm of managing expectations. This is ultimately your ability to control what people expect from you – and controlling those expectations means you are able to exceed them every time.

So first, to refresh your memory and provide a frame of reference, here’s the diagram from yesterday. When it comes to managing expectations, we can do it on all these levels, as we went through. If you under promise and over deliver, you will give customer surprise. It’s a hack job, but you’ll do it. What we need, though, is something more than this, and something which has more sustainability and long term strategy – and we find it is in customer suspense where expectation management really flourishes.

Suspense is, as we know, the experience of anticipating an experience. This can be the first time someone interacts with you, or it could be the nth time. Your ability to continue to place your customer in suspense and not merely surprise, satisfaction, or even sacrifice, comes from your ability to manage their expectations. The longer your go on with a customer, the easier it is for them to drop down the pyramid unless you innovate in the way your manage expectation.

Understanding suspense by looking at films

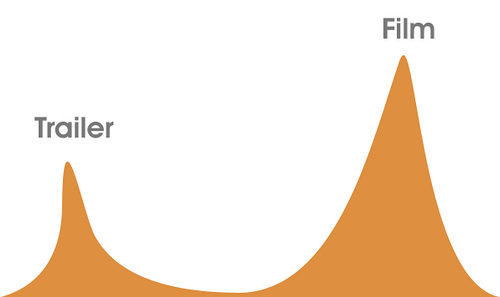

I think one of the best ways to understand suspense and expectation is with films. When the trailer for a film comes out, we have a peak of suspense because suddenly we are anticipating the experience of the film. This suspense spike lasts for a short while, and then goes dormant – until the film starts playing TV spots and other advertisements. We go to the see the film – and our suspense is the highest right before the film starts. From then on, we are now in the experience that we were anticipating, and based on our expectations, we will leave surprised, satisfied, or sacrificed.

This above diagram somewhat sums up what we experience for most films. But there are times when quite drastically, the trailer created more expectation than the film delivered, and we have sacrifice – the classic line being “all the best bits were in the trailer!”

This lesson of “the best bits were in the trailer” is first lesson in expectation management: what is your end?

In order to know what you have to give, you must take stock of what you’ve got. What is the sum total that your customer leaves with? Equally, you need to know what you will receive. You’ll see why in a moment.

Consider the following three scenarios:

1. A B-grade movie knows that it has a cheap storyline to give, and short-term ticket sales to receive. Given that its delivery is weak, it front-loads the best scenes into the trailer on purpose, to create expectations (suspense) that it knows it can’t meet, in order to get people in the cinema so the studio can receive its money. Important: even when they give their end away at the beginning, people still come thinking there is more. No matter how much you give away up front – people will always think there is more, even if there isn’t. So the studio makes lots on ticket receipts over a short period of time. They don’t even think about getting long-term revenue here. This is sacrifice.

2. Apple know that they have a great, game changing product to give, and years of sales and increased market share to receive. Therefore they release information to create a lot of expectation and buzz, but not more than they can deliver on. There’s the suspense. Then, they back-load the expectations. This means they keep the best stuff hidden They know that if they exceed expectations and surprise, they have done well, and even if they just meet expectations and satisfy, they have a very loyal fan base to receive sales from. They are actually more concerned with creating lots of suspense at the beginning to get people talking, than delivering a surprise on that suspense. This is surprise, or satisfaction.

A new café opens in town that already has a number of cafés. They know that they have a ‘newness’ factor, a unique selling point, and high standards from newly trained staff to give, and sales, a customer base, and permission to build long term loyalty with those customers, to receive. Given that they are new in town, they must not only satisfy expectations, but exceed them (surprise), to get customers to return and prefer them over their competitor. The first months are critical for them to continually surprise in order to lock in long term loyalty. This is surprise.

All this might seem like common sense, and it is. What each scenario highlights, however, is that once you know your end, and what you will receive, you know how much of the end to show, to get what you want to receive. A general rule of thumb is:

- If receiving short-term gain, front-load the expectations, in order to get numbers and sales in a spike.

- If receiving long-term gain, back-load the expectations, so that your over delivery gets people back for the next thing you do.

If you find that you’re running events, for example, but no one is coming back – then this may well be why. Why should they come back if you only satisfied them but didn’t surprise them? Given all the competition, if you only satisfy, then you lack uniqueness.

This is only a small part of expectation management, but it’s the start. Below I’ve given you a summary, and have asked specific questions from you. I’ll answer every question you ask to help you get better at this.

Actionable Summary

- Work out the sum total of what you have to give. This is called ‘the end‘.

- If you want to get short term gain, give away the end up front.

- If you want long term gain, give some of the end up front, but keep either a good portion, or the best portion, stored up.

Leading Questions

- Do you identify where you are failing, because you are not managing expectations?

- Does this model work with content marketing online? I’ve got a hunch that it does, but keen to hear your experience.

- Have you proven this model wrong? Are you having long term success by front-loading experience?

Archived Comments

-

munyaradzihoto

Could one argue that the trailer and the movie are two separate experiences so that the customer’s expectations of the trailer need to be managed before you even start managing the expectations that arise out of the trailer in anticipation of the movie?

As a framework it seems to me a logical progression and does seem to answer the question of how Apple has all of us wondering what’s coming next but how do businesses get over the fear of over-commitment to expectation management? That is to say, if we have to manage the expectations for the movie through the trailer, then we must manage the expectations of the trailer.. BUT THROUGH WHAT? and whatever we use as the preamble to the trailer needs to be managed so that we do not lose the customer early on.

Could it be argued that, with the above in mind, there are diminishing returns to expectation because it requires a lot of investment upfront for an investment that cannot be tangibly measured and even it if could be measured, what measure indicates captures the success or failure of the strategy since the outcome of expectation management is a FEELING? Shall we at this point use sales a as a metric? I think that argument was defeated yesterday.

So what is the way forward?

-

Scott Gould

Hi Munya, thanks for the comment.

So, yes, the trailer and the film are two separate experiences – and certainly on larger films, the trailer will require expectation management. And you can argue that in trilogies, each film is a separate experience of the whole trilogy. The important thing to remember, again, is “what is your end”? If the trailer is a marketing channel for the film, then it is subservient, and can only use the parts of the film.

Managing expectations before a trailer is then not only about marketing material, but about what has already gone before the film. Consider Marvel films – because there are already comics, there is far more anticipation.

Your final point is interesting – and I believe that are now able to begin tangible measure expectation through sentiment and intent analysis online. This means monitoring tweets, facebook, blogs, and seeing how the sentiment and intent changes through a campaign.

Comments